Britain and America have had more than their fair share of great [English language] comedians over the years but it’s fair to say that Australia has never been world renowned in this field.

Two exceptions immediately spring to mind – Barry Humphries and Garry McDonald, one from Melbourne and one from Sydney.

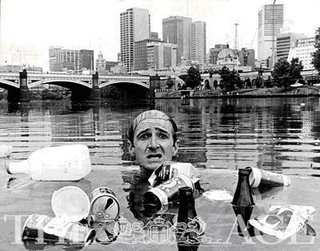

Fearless reporter Norman Gunston [Garry McDonald] reporting on pollution in Melbourne’s Yarra River [The Age newspaper, Melbourne]

Garry McDonald’s humour spanned the 70s and 80s, and his most famous alter-ego, Norman Gunston, is best summed up by the ABC’s Nostalgia Central:

Conceived by Aunty Jack Show writer Wendy Skelcher, Norman Gunston, trooly rooly took on a life of his own. The hapless reporter tackled the big names in show biz, including a laughing Ray Charles and an unamused Rudolph Nureyev.

Gunston's hysterical interviews with the likes of Frank Zappa, Paul and Linda McCartney, Sally Struthers, Keith Moon (who responded by pouring champagne over Norman's head) and later, Kiss, are the stuff of legend.

The character of Norman Gunston was brought to life by accomplished character actor Garry McDonald, who already had a string of successes to his name.

McDonald was never afraid to make Gunston an appallingly dressed fall guy, who couldn’t even shave properly in the morning and Norman's real talent was in being able to bamboozle and confound his interview subjects with his seemingly ignorant and naïve satire.

He also managed to carve quite a musical career for himself in the 70s, before moving on to the internationally celebrated sitcom series, Mother & Son, with the late, great Ruth Cracknell.

One famous interview with British actress Sally Struthers remains a classic. When Norman tried to interview her, she pointed to his shaving cuts and the bits of toilet paper dotting his face and seriously advised him to use an electric razor.

"I do." he looked down, pitifully.

That just about finished her off. She fell back on the interview chair, convulsed with laughter and couldn’t speak for about two minutes.

Some Garry McDonald [Norman] classics include:

1. [to Linda McCartney]: "It's funny- you don't look Japanese."

2. [to Paul McCartney]: "Was there any truth in the 1968 rumours about your death?"

3. [to Mick Jagger]: "Do you have any regrets about leaving the Beatles?"

4.[again to Mick Jagger, asking about his recent arrest for drug possession]: "Between you and me - where were the drugs - under the bed?"

5. [to Hugh Hefner, founder of Playboy]: "Well I once took a rude picture you could have used in your magazine. My Aunt Naomi was bending down to tie up her tennis shoes and … well … I needed to finish the roll of film."

.o0o.

Barry Humphries was born in suburban Melbourne in 1934 but moved to London at 25, honing his comedy to a fine point.

Educated at the elite Melbourne Grammar School, he was noted for his stunts, one of the more memorable being to take an ordinary suburban commuter train to work in the morning at peak hour and at every station along the line, high-toned waiters would step on board to serve him silver service breakfast. At the end of the line, he folded his napkin and stepped off the train.

"Entertaining people gave me a great feeling of release - making people laugh was a very good way of befriending them. People couldn't hit you, could they, if they were laughing?"

He has been instrumental in defining the archetypal Australian word ‘ratbag’. The dictionary defines it as: "a mean, despicable person."

He redefined this as: "someone who does not behave properly", maybe someone highly individual or out of step with society. He went on to create various confrontational, egotistical, yet somehow loveable, satirical characters who seem to have, over time, become as real as their creator.

His most famous and enduring creation was Melbourne housewife, Dame Edna Everage, [internationally celebrated Megastar], who achieved worldwide fame for both herself and her creator. Her greeting to adoring audiences, 'Hello possums!' is now a part of the lexicon.

Humphries is also regarded as one of the country's best landscape artists and is the award winning author of several plays, books, novels, and autobiographies. A recipient of the Order of Australia in 1982, he is married to Lizzie, the daughter of British poet Sir Stephen Spender, and has two sons and two daughters.

Quotes

As Edna: "I was born with a precious gift - the ability to laugh at the misfortune of others."

To actress Jane Seymour: "Now Jane, you’ve been successfully married three times – can you tell the viewers the secret of a happy marriage?"

In Vanity Fair: "Forget Spanish. There's nothing in that language worth reading except Don Quixote. Study French or German if you must or, if you're an American, you could try learning English."

Other quotes: "Australia is an outdoor country. People only go inside to use the toilet and that's only a recent development."

The real Barry Humphries

"There is no more terrible fate for a comedian than to be taken seriously."

"I have a greedy attitude to life and I think that's not altogether bad. So I'm waiting for something quite unexpected and joyful to happen to me...and it probably will."

"I’d like to think I’ve encouraged people to look at Australia critically, with affection and humour; which is what all comedians should do."

Barry Humphries delivered a speech on October 6th, 2005, at the 20th anniversary dinner of the Committee for Melbourne. This is an abridged version:

Barry Humphries as himself

“LESS than a year after Hitler became chancellor of the Third Reich, I was born in Melbourne.

My birthplace was an ugly red-brick hospital in Kew and it was often pointed out to me by my parents whenever we went, like everyone else in Melbourne, for our Sunday afternoon spin in the Oldsmobile.

The purpose of these excursions was to look at the "lovely homes" and my father, being in the building trade, took more than a sentimental interest in the new cream brick villas that were springing up on the slopes of Eaglemont and Balwyn.

Indeed, the very parts of Melbourne that Streeton and Roberts and Conder had so lovingly painted in the 1890s were the ones Melbourne most enthusiastically now sought to obliterate.

Years later, some planning committee must have looked at the Yarra Valley and still detected a vestige of its former beauty, so they gleefully finished the job with the six-lane Eastern Freeway.

I was really more interested in slums, and on every Sunday drive I implored my father to let me see some.

It must be remembered that my parents were a post-Depression couple who came from the working-class suburb of Thornbury and thanks to the growing success of my father's business they had moved to Camberwell on the fringes of the metropolitan area.

Slums were the last things my parents wanted to be reminded of, though I was sure they existed somewhere at a place called Dudley Flats. We never went there.

"Don't forget," my mother said, "that poor people can also be quite nice."

I was reminded of my mother the other day when Barbara Bush, speaking of the victims of hurricane Katrina, said publicly: "But they were under-privileged anyway."

"Look at that little home," my mother once exclaimed, urging my father to reduce his speed to a kerb crawl. It was a drab little weatherboard semi with a scrap of iron lace on the veranda but with a gleaming brass doorknob.

"See how they've polished that brass," my mother said, "and see how clean the windows are. You don't have to be rich to be particular", at which my father would quickly accelerate, and soon, with a collective sigh, we would be back in the leafy streets of East Camberwell, lined with elms and plane trees and nice houses with a decent setback.

I used to bicycle to my prep school through those streets in the autumn, my favourite month, when cars were few and when the leaves were swept into pyramids to be burnt. The later banning of autumnal bonfires of leaves was a death blow to the aromatic Melbourne of my youth.

When I was moved by my parents to an expensive school in South Yarra, the transport arrangements were more complicated. Usually I took a suburban train to Flinders Street and a tram along St Kilda Road.

The train ride into town in a first class non-smoker was always a good reading opportunity and the compartments, with their green banquettes, were embellished with railway murals of Victoria’s beauty spots, none of which ever made me wish to visit the beauty spots depicted.

I was more interested in going to England, a mythical place full of castles, thatched cottages, Beefeaters and Winston Churchill.

In those days, there was an image of Churchill in almost every Australian home but you would have to visit the opportunity shops of Melbourne to find a Churchill Toby jug today.

The noticeable thing about the men and also the women who waited for the train on Willison Station was that they wore hats; workmen in particular. They could be seen rolling their own cigarettes and the older men often sported a returned serviceman's badge.

They always carried battered Gladstone bags, in which one presumed were sandwiches, wrapped in greaseproof paper and a copy of The Sporting Globe, Truth or Smith's Weekly.

These last two newspapers were banned at our house and I had only glimpsed their salacious contents when I visited Mr McGrath the barber, for a brutal short-back-and-sides.

The women on the station not only wore hats, but also gloves, for they were going into the city after all, whereas the proletarians would probably alight where the factories were at Richmond and Burnley, when after work, those collapsed Gladstone bags would accommodate six bottles of Abbots Lager.

Going into the city was always a ritual I enjoyed with my mother, for it meant hats, gloves, crumbed whiting [fish] at the Wattle Tea Rooms or creamed sweet corn (undoubtedly out of a tin) at Russell Collins. We would only shop in Collins Street.

Bourke Street was thought common and there were second hand bookshops around the eastern market — a paradise for germs.

I was still growing up in Melbourne when the '50s dawned, an era I have since called The Age Of Laminex. Australia had never been cleaner. Washing powders had yet to be called "detergents" and were still, prosaically, soap but the Bendix washer arrived at about the same time as the Biro [ballpoint pen].

Ballpoint pens were banned at Melbourne Grammar, since they destroyed calligraphy, though very few old Melburnians went on to write anything more interesting than cheques.

The new washing machines replaced the old fashioned copper and trough where boiled and soapy sheets were poked with copper sticks.

You won't find a copper stick in the opportunity shop today, though of course there are plenty of jaffle irons [a '50s invention for toasting sandwiches] among the fondue sets that young married couples received in multiples on their darkest day.

I was there in Carlton for the arrival of the espresso machine and the quaintly mispronounced "cuppachino" and when I worked for nearly a year at EMI in Flinders Lane - without ever knowing what the initials EMI stood for - I was present at the birth of the long-playing, microgroove record.

One of the most important Melbourne spectacles of this period was an establishment in Swanston Street, opposite St Paul's Cathedral, called Downey Flake.

Here crowds pressed against the window awestruck to observe an enormous stainless steel machine which stirred a vat of yellow sludge, scooped dollops onto a conveyer belt and dropped calamari like rings into a cauldron of seething fat from which emerged, on another belt, an endless succession of sugared doughnuts.

By the end of the decade there would be a television set in every house in Melbourne. The Best Room, often called "The Lounge Room", where paradoxically, no one was ever allowed to lounge or even relax, became a ghost room.

At the back of the house, the family huddled before the new instrument and driving down a Melbourne suburban street one evening in 1960, you would at first suppose it to be deserted; its inhabitants fled or evaporated like the crew of the Marie Celeste.

Yet, above the rooftops, when you looked a second time, was a bluish grey flicker, the shimmering Aurora Australis of television, the only Australian art form that never disappointed its public by improving.

I missed the 1956 Melbourne Olympic Games but they changed Melbourne. This was the heyday of Whelan the Wrecker, a family demolition firm that proudly emblazoned its name over every act of civic vandalism in the '50s and '60s when some of our best Victorian architecture disappeared.

Some of my favourite old bookshops vanished as well. Used books harboured bacteria after all, and it would give visitors to Melbourne a very bad impression if it were implied that we couldn't afford new books.

However there were still exciting art exhibitions in Melbourne that didn't happen anywhere else in Australia. The city was full of commercial art galleries, now forgotten.

The trams were still an attractive cream and green as they had been since the 1930s when the colours were first suggested as the result of a state-wide competition.

I am not sure when Moomba [the provincial street parade] was invented but it has to have been in the '50s. We were told it was an Aboriginal word meaning "let's get together and have fun". Mrs Edna Everage said that it was a word that the Aborigines gave us when they had no further use for it.

There were also kings and queens of Moomba, now long forgotten. It was probably the synthetic gaiety of Moomba that persuaded me to leave Melbourne in 1959 for my travels and adventures abroad.

The boat, an Italian one, sailed from Port Melbourne to Venice, but I already had a taste for things Italian. After all, I had already mingled with the sophisticated crowd who hung out at the Florentino Bistro eating Spaghetti ala Bolognese and drinking Chianti.

I have lately been touring the Midwest of the United States and visited cities in serious urban decay. By contrast, what a pleasure it is to stroll through the streets of Melbourne safely at night, to visit small restaurants and to take coffee or browse in the bookstores.

It is a sign of progress that I have been asked to address you at all on the subject of my home town. I was long dismissed as a traitor, or worse, an expatriate, merely because I recognised the intrinsic bittersweet comedy of suburban life.

On a visit to Vienna recently I met an old museum guide who had come to Australia as a migrant in the '50s.

"You see, sir," said the old guide, gazing wistfully out of the window at the dying light on Stephan's Dom, "I stand here all day dreaming of … Broadmeadows" [one of the blandest Melbourne suburbs].

He made it seem so romantic that it has now become a place on the map of Melbourne that still awaits my pilgrimage.

Two exceptions immediately spring to mind – Barry Humphries and Garry McDonald, one from Melbourne and one from Sydney.

Fearless reporter Norman Gunston [Garry McDonald] reporting on pollution in Melbourne’s Yarra River [The Age newspaper, Melbourne]

Garry McDonald’s humour spanned the 70s and 80s, and his most famous alter-ego, Norman Gunston, is best summed up by the ABC’s Nostalgia Central:

Conceived by Aunty Jack Show writer Wendy Skelcher, Norman Gunston, trooly rooly took on a life of his own. The hapless reporter tackled the big names in show biz, including a laughing Ray Charles and an unamused Rudolph Nureyev.

Gunston's hysterical interviews with the likes of Frank Zappa, Paul and Linda McCartney, Sally Struthers, Keith Moon (who responded by pouring champagne over Norman's head) and later, Kiss, are the stuff of legend.

The character of Norman Gunston was brought to life by accomplished character actor Garry McDonald, who already had a string of successes to his name.

McDonald was never afraid to make Gunston an appallingly dressed fall guy, who couldn’t even shave properly in the morning and Norman's real talent was in being able to bamboozle and confound his interview subjects with his seemingly ignorant and naïve satire.

He also managed to carve quite a musical career for himself in the 70s, before moving on to the internationally celebrated sitcom series, Mother & Son, with the late, great Ruth Cracknell.

One famous interview with British actress Sally Struthers remains a classic. When Norman tried to interview her, she pointed to his shaving cuts and the bits of toilet paper dotting his face and seriously advised him to use an electric razor.

"I do." he looked down, pitifully.

That just about finished her off. She fell back on the interview chair, convulsed with laughter and couldn’t speak for about two minutes.

Some Garry McDonald [Norman] classics include:

1. [to Linda McCartney]: "It's funny- you don't look Japanese."

2. [to Paul McCartney]: "Was there any truth in the 1968 rumours about your death?"

3. [to Mick Jagger]: "Do you have any regrets about leaving the Beatles?"

4.[again to Mick Jagger, asking about his recent arrest for drug possession]: "Between you and me - where were the drugs - under the bed?"

5. [to Hugh Hefner, founder of Playboy]: "Well I once took a rude picture you could have used in your magazine. My Aunt Naomi was bending down to tie up her tennis shoes and … well … I needed to finish the roll of film."

.o0o.

Barry Humphries was born in suburban Melbourne in 1934 but moved to London at 25, honing his comedy to a fine point.

Educated at the elite Melbourne Grammar School, he was noted for his stunts, one of the more memorable being to take an ordinary suburban commuter train to work in the morning at peak hour and at every station along the line, high-toned waiters would step on board to serve him silver service breakfast. At the end of the line, he folded his napkin and stepped off the train.

"Entertaining people gave me a great feeling of release - making people laugh was a very good way of befriending them. People couldn't hit you, could they, if they were laughing?"

He has been instrumental in defining the archetypal Australian word ‘ratbag’. The dictionary defines it as: "a mean, despicable person."

He redefined this as: "someone who does not behave properly", maybe someone highly individual or out of step with society. He went on to create various confrontational, egotistical, yet somehow loveable, satirical characters who seem to have, over time, become as real as their creator.

His most famous and enduring creation was Melbourne housewife, Dame Edna Everage, [internationally celebrated Megastar], who achieved worldwide fame for both herself and her creator. Her greeting to adoring audiences, 'Hello possums!' is now a part of the lexicon.

Humphries is also regarded as one of the country's best landscape artists and is the award winning author of several plays, books, novels, and autobiographies. A recipient of the Order of Australia in 1982, he is married to Lizzie, the daughter of British poet Sir Stephen Spender, and has two sons and two daughters.

Quotes

As Edna: "I was born with a precious gift - the ability to laugh at the misfortune of others."

To actress Jane Seymour: "Now Jane, you’ve been successfully married three times – can you tell the viewers the secret of a happy marriage?"

In Vanity Fair: "Forget Spanish. There's nothing in that language worth reading except Don Quixote. Study French or German if you must or, if you're an American, you could try learning English."

Other quotes: "Australia is an outdoor country. People only go inside to use the toilet and that's only a recent development."

The real Barry Humphries

"There is no more terrible fate for a comedian than to be taken seriously."

"I have a greedy attitude to life and I think that's not altogether bad. So I'm waiting for something quite unexpected and joyful to happen to me...and it probably will."

"I’d like to think I’ve encouraged people to look at Australia critically, with affection and humour; which is what all comedians should do."

Barry Humphries delivered a speech on October 6th, 2005, at the 20th anniversary dinner of the Committee for Melbourne. This is an abridged version:

Barry Humphries as himself

“LESS than a year after Hitler became chancellor of the Third Reich, I was born in Melbourne.

My birthplace was an ugly red-brick hospital in Kew and it was often pointed out to me by my parents whenever we went, like everyone else in Melbourne, for our Sunday afternoon spin in the Oldsmobile.

The purpose of these excursions was to look at the "lovely homes" and my father, being in the building trade, took more than a sentimental interest in the new cream brick villas that were springing up on the slopes of Eaglemont and Balwyn.

Indeed, the very parts of Melbourne that Streeton and Roberts and Conder had so lovingly painted in the 1890s were the ones Melbourne most enthusiastically now sought to obliterate.

Years later, some planning committee must have looked at the Yarra Valley and still detected a vestige of its former beauty, so they gleefully finished the job with the six-lane Eastern Freeway.

I was really more interested in slums, and on every Sunday drive I implored my father to let me see some.

It must be remembered that my parents were a post-Depression couple who came from the working-class suburb of Thornbury and thanks to the growing success of my father's business they had moved to Camberwell on the fringes of the metropolitan area.

Slums were the last things my parents wanted to be reminded of, though I was sure they existed somewhere at a place called Dudley Flats. We never went there.

"Don't forget," my mother said, "that poor people can also be quite nice."

I was reminded of my mother the other day when Barbara Bush, speaking of the victims of hurricane Katrina, said publicly: "But they were under-privileged anyway."

"Look at that little home," my mother once exclaimed, urging my father to reduce his speed to a kerb crawl. It was a drab little weatherboard semi with a scrap of iron lace on the veranda but with a gleaming brass doorknob.

"See how they've polished that brass," my mother said, "and see how clean the windows are. You don't have to be rich to be particular", at which my father would quickly accelerate, and soon, with a collective sigh, we would be back in the leafy streets of East Camberwell, lined with elms and plane trees and nice houses with a decent setback.

I used to bicycle to my prep school through those streets in the autumn, my favourite month, when cars were few and when the leaves were swept into pyramids to be burnt. The later banning of autumnal bonfires of leaves was a death blow to the aromatic Melbourne of my youth.

When I was moved by my parents to an expensive school in South Yarra, the transport arrangements were more complicated. Usually I took a suburban train to Flinders Street and a tram along St Kilda Road.

The train ride into town in a first class non-smoker was always a good reading opportunity and the compartments, with their green banquettes, were embellished with railway murals of Victoria’s beauty spots, none of which ever made me wish to visit the beauty spots depicted.

I was more interested in going to England, a mythical place full of castles, thatched cottages, Beefeaters and Winston Churchill.

In those days, there was an image of Churchill in almost every Australian home but you would have to visit the opportunity shops of Melbourne to find a Churchill Toby jug today.

The noticeable thing about the men and also the women who waited for the train on Willison Station was that they wore hats; workmen in particular. They could be seen rolling their own cigarettes and the older men often sported a returned serviceman's badge.

They always carried battered Gladstone bags, in which one presumed were sandwiches, wrapped in greaseproof paper and a copy of The Sporting Globe, Truth or Smith's Weekly.

These last two newspapers were banned at our house and I had only glimpsed their salacious contents when I visited Mr McGrath the barber, for a brutal short-back-and-sides.

The women on the station not only wore hats, but also gloves, for they were going into the city after all, whereas the proletarians would probably alight where the factories were at Richmond and Burnley, when after work, those collapsed Gladstone bags would accommodate six bottles of Abbots Lager.

Going into the city was always a ritual I enjoyed with my mother, for it meant hats, gloves, crumbed whiting [fish] at the Wattle Tea Rooms or creamed sweet corn (undoubtedly out of a tin) at Russell Collins. We would only shop in Collins Street.

Bourke Street was thought common and there were second hand bookshops around the eastern market — a paradise for germs.

I was still growing up in Melbourne when the '50s dawned, an era I have since called The Age Of Laminex. Australia had never been cleaner. Washing powders had yet to be called "detergents" and were still, prosaically, soap but the Bendix washer arrived at about the same time as the Biro [ballpoint pen].

Ballpoint pens were banned at Melbourne Grammar, since they destroyed calligraphy, though very few old Melburnians went on to write anything more interesting than cheques.

The new washing machines replaced the old fashioned copper and trough where boiled and soapy sheets were poked with copper sticks.

You won't find a copper stick in the opportunity shop today, though of course there are plenty of jaffle irons [a '50s invention for toasting sandwiches] among the fondue sets that young married couples received in multiples on their darkest day.

I was there in Carlton for the arrival of the espresso machine and the quaintly mispronounced "cuppachino" and when I worked for nearly a year at EMI in Flinders Lane - without ever knowing what the initials EMI stood for - I was present at the birth of the long-playing, microgroove record.

One of the most important Melbourne spectacles of this period was an establishment in Swanston Street, opposite St Paul's Cathedral, called Downey Flake.

Here crowds pressed against the window awestruck to observe an enormous stainless steel machine which stirred a vat of yellow sludge, scooped dollops onto a conveyer belt and dropped calamari like rings into a cauldron of seething fat from which emerged, on another belt, an endless succession of sugared doughnuts.

By the end of the decade there would be a television set in every house in Melbourne. The Best Room, often called "The Lounge Room", where paradoxically, no one was ever allowed to lounge or even relax, became a ghost room.

At the back of the house, the family huddled before the new instrument and driving down a Melbourne suburban street one evening in 1960, you would at first suppose it to be deserted; its inhabitants fled or evaporated like the crew of the Marie Celeste.

Yet, above the rooftops, when you looked a second time, was a bluish grey flicker, the shimmering Aurora Australis of television, the only Australian art form that never disappointed its public by improving.

I missed the 1956 Melbourne Olympic Games but they changed Melbourne. This was the heyday of Whelan the Wrecker, a family demolition firm that proudly emblazoned its name over every act of civic vandalism in the '50s and '60s when some of our best Victorian architecture disappeared.

Some of my favourite old bookshops vanished as well. Used books harboured bacteria after all, and it would give visitors to Melbourne a very bad impression if it were implied that we couldn't afford new books.

However there were still exciting art exhibitions in Melbourne that didn't happen anywhere else in Australia. The city was full of commercial art galleries, now forgotten.

The trams were still an attractive cream and green as they had been since the 1930s when the colours were first suggested as the result of a state-wide competition.

I am not sure when Moomba [the provincial street parade] was invented but it has to have been in the '50s. We were told it was an Aboriginal word meaning "let's get together and have fun". Mrs Edna Everage said that it was a word that the Aborigines gave us when they had no further use for it.

There were also kings and queens of Moomba, now long forgotten. It was probably the synthetic gaiety of Moomba that persuaded me to leave Melbourne in 1959 for my travels and adventures abroad.

The boat, an Italian one, sailed from Port Melbourne to Venice, but I already had a taste for things Italian. After all, I had already mingled with the sophisticated crowd who hung out at the Florentino Bistro eating Spaghetti ala Bolognese and drinking Chianti.

I have lately been touring the Midwest of the United States and visited cities in serious urban decay. By contrast, what a pleasure it is to stroll through the streets of Melbourne safely at night, to visit small restaurants and to take coffee or browse in the bookstores.

It is a sign of progress that I have been asked to address you at all on the subject of my home town. I was long dismissed as a traitor, or worse, an expatriate, merely because I recognised the intrinsic bittersweet comedy of suburban life.

On a visit to Vienna recently I met an old museum guide who had come to Australia as a migrant in the '50s.

"You see, sir," said the old guide, gazing wistfully out of the window at the dying light on Stephan's Dom, "I stand here all day dreaming of … Broadmeadows" [one of the blandest Melbourne suburbs].

He made it seem so romantic that it has now become a place on the map of Melbourne that still awaits my pilgrimage.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments need a moniker of your choosing before or after ... no moniker, not posted, sorry.